Mobile Computing

May 20, 2014 Leave a comment

Many have predicted the fall of the PC in favor of large-scale mobile computing with smartphones and tablets. Most people don’t need the power of a high-end laptop or desktop computer to check email and play Facebook games. Indeed, most services are now provided over the Internet, with low client computational requirements. However, we may see an abrupt reversal in this trend.

There are two factors at play that could radically change the direction of the computing market. First, some experts are now predicting doom and gloom for the “free Internet”. The post-Snowden Internet is very likely going to fragment along national lines, with each country creating its own insulated network over security concerns. Not only does this mean the US will lose its disproportionate share of Internet business (and US tech companies will see significant declines in overseas sales), but it also means the era of cloud services may be coming to a premature close. As users see the extent of NSA data mining, they may become less willing to keep all of their data with a potentially unsecured third-party. If users wish to start doing more computing offline – or at least locally – in the name of security, then desktop computers and high-power tablets may see a boost in sales.

Second, the gulf between “PCs” and “tablets” is rapidly closing; the agony over PC-mobile market shifts will soon be moot. Seeing a dip in traditional PC sales, many manufacturers have branched out, and are now creating a range of hybrid devices. These are often large tabletop-scale tablets to replace desktops, or tablets like the Surface Pro to replace laptops. I suspect the PC market will fragment, with a majority of sales going towards these PC-mobile hybrids, and a smaller percentage going towards specialty desktops for high-power gaming and industry work (think CAD and coding).

I doubt desktop computers will disappear. In 10 years, the average household might have a large tablet set in a holder on a desk and connected to a mouse and keyboard, or laid flat on a coffee table. It would be used for playing intensive computer games, or the entire family could gather round and watch videos. In addition to this big tablet-computer, each person would have one or two “mobile” devices: a smallish smartphone, and a medium tablet with a keyboard attachment that could turn it into laptop-mode. Some people may opt for a large-screen phone and forgo the tablet.

It’s hard to tell whether or not the revelations about national spying will significantly impact the civilian net (the same goes for the fall of net neutrality). On the one hand, people are concerned about the security of their data. However, being able to access data from any device without physically carrying it around has proved to be a massive game-changer for business and society in general. We may be past the point-of-no-return when it comes to adopting a cloud computing framework. On the whole, transitioning from a dichotomy between “mobile devices” and “computers” to a spectrum of portability seems to be a very good thing.

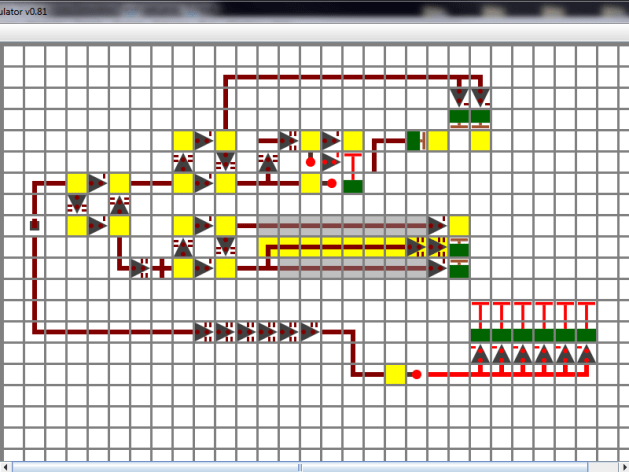

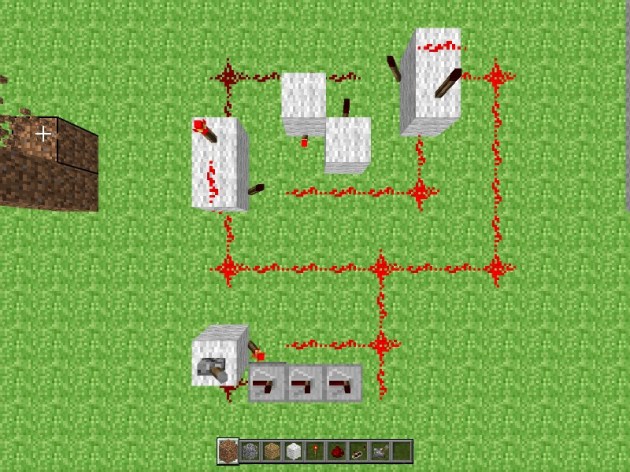

Minecraft, on the other hand, is about as physically unrealistic as you can get. However, it provides an awesome way to teach logic and economics. Even vanilla Minecraft has a growing arsenal of parts which allow rudimentary (or not so rudimentary) automation. Redstone is a powerful tool for doing any sort of logical manipulation — or teaching it. Watching your toolbox of gates and mechanisms grow out of a few basic ground rules is amazing. Creative minds are pushed to imagining new ways of using redstone, pistons, minecarts, and all the other machines being added in. While

Minecraft, on the other hand, is about as physically unrealistic as you can get. However, it provides an awesome way to teach logic and economics. Even vanilla Minecraft has a growing arsenal of parts which allow rudimentary (or not so rudimentary) automation. Redstone is a powerful tool for doing any sort of logical manipulation — or teaching it. Watching your toolbox of gates and mechanisms grow out of a few basic ground rules is amazing. Creative minds are pushed to imagining new ways of using redstone, pistons, minecarts, and all the other machines being added in. While