NASA’s Asteroid Retrieval Mission…

September 18, 2014 Leave a comment

…is actually pretty cool. People who are un-enthused by the idea (including many NASA employees) are clearly focusing on the wrong aspect.

First, let me give an objective overview of the mission.

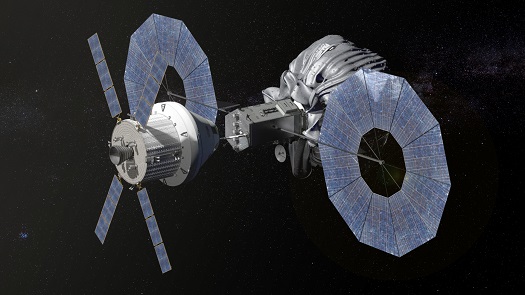

“NASA plans to launch the ARM robotic spacecraft at the end of this decade. The agency is working on two concepts for the capture: one would capture an asteroid using an inflatable system, similar to a bag, and the other would capture a boulder off of a much larger asteroid using a robotic arm. The agency will choose one of the two concepts in late 2014.

After an asteroid mass is captured, the spacecraft will redirect it to a stable orbit around the moon called a “Distant Retrograde Orbit.” Astronauts aboard NASA’s Orion spacecraft, launched from a Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, will explore the asteroid in the mid-2020s.”

–NASA

So, to summarize: we are going to move a giant space rock from it’s orbit around the sun to an orbit around the moon. A space boulder. We are moving it into orbit around the Moon. Does nobody else think that is a HUGE DEAL? The closest thing we’ve ever done is maybe return little grains of dirt from an asteroid. Except this time its an honest-to-god celestial body. That we are moving from one ORBIT to another. Oh, and then I guess we’re sending people to it or something.

Honestly, the manned mission is just shoe-horned in to appease NASA’s mandated directives. The star of the show here is the spacecraft that is moving an asteroid larger than itself (if you don’t count the bag or solar panels — I’m sure the bag can be swapped out for some sort of thermal lance). The advances in electric propulsion and in-space engineering alone will be astounding. Just think of the applications for ISRU (in situ resource utilization) and orbital manufacturing this will provide.

The ability to drag a study target into an easier-to-reach orbit is stupendous. For one, it means we can send a number of heavier, less expensive unmanned missions to study different aspects of it, with more launch windows and shorter commute times. We can get an extensive profile of the object (even drilling inside), to a level of detail we couldn’t obtain if we were sending a small probe out to the asteroid’s ‘native’ environment.

Having this technology is great for both diverting hazardous asteroids and studying a number of different asteroids at decreased expense. Instead of sending a heavy science probe off using the SLS, we send a re-director up to drag the asteroid close, even into LEO, and then send up a bunch of heavy science probes using cheaper rockets. Alternatively, dragging an asteroid into orbit would be a great opportunity to prototype asteroid-mining techniques.

The point is that if you think putting an asteroid into orbit around the moon is a lame excuse to use the poorly-thought-out Orion/SLS system, you are absolutely right. An Apollo-style mission architecture doesn’t work for anything beyond a Moon mission, so it’s pointless to think of this mission as “training” for anything. But just because visiting an asteroid with people is pointless doesn’t mean that dragging an asteroid into lunar orbit and visiting it whatsoever is a fruitless exercise. There is IMMENSE value in an asteroid retrieval mission. Seriously, it’s as exciting as a submarine to Europa or Titan.