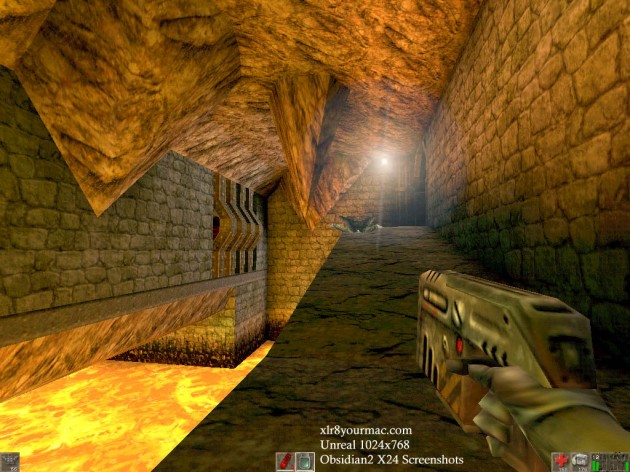

Valve’s Source and GoldenSource engines and Epic’s Unreal engines have had a long, acrimonious feud. Both Golden Source and the Unreal Engine debuted in 1998 in Half Life and Unreal, respectively. Both were considered revolutionary games at the time. Unreal blew technical and graphical expectations out of the water. Half Life left a legacy as one of the most influential games in the FPS genre.

Fast forward 6 years. Valve, in the meantime, has released Team Fortress Classic and Counterstrike, both extremely revolutionary games. The Unreal and Unreal 2 engines (the latter was released 2 years prior) had become extremely popular platforms for game developers, mostly because of the engines’ notable modularity and room for modification.

In 2004, Valve debuts the Source engine with Half Life 2, a ground breaking game that completely demolishes competition and sets a long-lasting legacy in terms of story, gameplay, and graphics. For comparison, Unreal Tournament 2004 was published the same year.

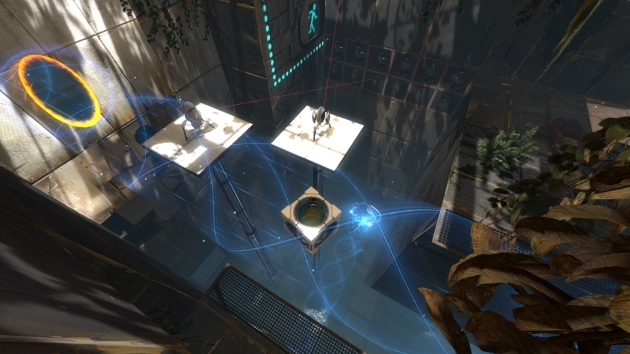

In another 7 years, Unreal Engine 3 has been released and games like Gears of War and Batman: Arkham City have been developed using it. Valve has just published their first widely supported game, Portal 2. The Source engine has been evolved over the years, and many graphical upgrades have been applied along with compatibility with major game consoles.

However, it becomes readily apparent that the visual styles of these two engines have diverged in the years since 1998. The Unreal line of engines have supported games like Bioshock and Mass Effect, but have also bourn the brunt of AAA games. Such games are known for their muted brown-grey color pallete, uninteresting story, and factory-made gameplay. Unreal Engine games are commonly criticized for having character models that look “plastic” (a result of game developers setting specular too high on materials), awkward character animations, and overuse of lens flares and bloom.

Games on the Source engine, on the other hand, consistently revolutionize some aspect of gaming. For example, Team Fortress 2, Portal, and Left 4 Dead are widely known for innovative gameplay. Unfortunately, Valve has lagged behind in terms of pushing the graphical frontier. Half Life 2 was smashingly good for its time, much in the same way that Halo stunned the gaming world back in 2001. However, every Source game since its debut has looked more and more aged.

Even worse, developers are driven away from using the Source engine due to a set of tools that have barely evolved since they were developed in 1998. Hammer, the level creation program, and Face Poser, the character animation blender, are unwieldy and unfinished; Source SDK tools are notorious for their bugs and frequent crashes.

Conversely, the Unreal toolset is streamlined and easy to jump into. This appeal has drawn more and more amateurs and professional developers alike. The editor allows you to pop right into the game to see changes, whereas the Source engine still requires maps to be compiled (which can take minutes) in order for the most recent revision to be played. Unreal’s deformable meshes dwarf the Source engine’s awkward displacement system.

However, I have a feeling that a couple of factors are going to come together and boost both engines out of the recent stigma they have incurred. The biggest factor is that at some point the AAA game industry is going to collapse. The other critical event is Half Life 3.

Yes! Do I know something you don’t? Have I heard a rumor lurking the Internet about this mysterious game? No. But I do know history. And that is more useful than all the forum threads in the universe.

Half Life was released in 1998. Half Life 2 was released in 2004. Episode 2 was released in 2007. Half Life 2 took 6 years to develop, despite being on a side burner for some of that time. By extrapolation, Half Life 3 should be nearing release in the next 2 years. However, circumstances are different.

The Source engine was developed FOR Half Life 2. Graphics were updated. But the toolset remained the same. In the time between HL2 and now, Valve has been exploring other genres. Team Fortress 2, Portal 2, and Left 4 Dead 2 all took a portion of the company’s resources. In addition, that last few years have been spent intensively on developing Dota 2 (which, by the way, was the cause of the free release of Alien Swarm). The second Counterstrike was contracted out. So Half Life 3 has been a side project, no doubt going through constant revisions and new directions.

However, unless Valve is going to release Day of Defeat 2 or Ricochet 2 (yeah right) in 2013, production on Half Life 3 is going to kick into high gear. There is one fact that drives me to believe even more heavily in this theory.

Since 2011, and probably even earlier, Valve has been pumping a huge amount of effort into redesigning their entire suite of development tools. It had become readily apparent to everyone at the company that the outdated tools were making it impossible to develop games efficiently.

“Oh yeah, we’re spending a tremendous amount of time on tools right now. So, our current tools are… very painful, so we probably are spending more time on tools development now than anything else and when we’re ready to ship those I think everybody’s life will get a lot better. Just way too hard to develop content right now, both for ourselves and for third-parties so we’re going to make enormously easier and simplify that process a lot.”

-Gabe Newell

Because both TF2 and Portal 2 have been supported continuously since their release, they have been the first to see the effects of this new tool development. Valve seems to have used these games as testing grounds, not only for their Free to Play business model and Steam Workshop concept, but also for new kinds of development tools. First, the Portal 2 Puzzle Maker changed the way that maps were made. In the same way that Python streamlines the programming process, the Puzzle Maker cuts out the tedious technical parts of making a level.

The second tool released was the Source Filmmaker. Although it doesn’t directly influence the way maps are made, its obviously been the subject of a lot of thought and development. The new ways of thinking about animation and time introduced by the SFM are probably indicative of the morphing paradigms in the tool development section at Valve.

Don’t think that Valve is going to be trampled by any of its competitors. Despite Unreal Engine’s public edge over the Source engine, especially with the recent UE4 reveal, the AAA game industry is sick, and no other publisher has a grip on the PC game market quite like Valve does. And although 90% of PC gamers pirate games, PC game sales are hardly smarting. In fact, the PC game market is hugely profitable, racking up $19 billion in 2011. This is just a few billion shy of the collective profits of the entire console market. Yet the next best thing to Steam is, laughably, EA’s wheezing digital content delivery system Origin.

Numbers Source

Anyways, here’s hoping for Half Life 3 and a shiny new set of developer tools!